Earlier this year we were delighted to be able to facilitate a Pedagogy workshop with Helen Elliot, Teaching Fellow and PGCE/PGDE Secondary History Subject Tutor at Birmingham City University and Martin Phillips the Local Heritage Education Manager (West Midlands), Heritage Schools, for Historic England. The workshop, facilitated by Corinna Rayner, the Archives & Collections Manager, was all about planning a series of lessons around a theme based on Birmingham’s History and used resources held in the Library of Birmingham’s Archives. As we were still in lockdown, the workshop was digital – and while it worked really well – we do hope to be able run it again for next year’s students… in the Library of Birmingham building!

What follows is a blog from Helen Elliot (and the students), following on from that workshop, providing advice to teachers of History in secondary schools.

In my teenage years I was something of a family history nerd, which happily coincided with the expansion in availability of archives and records online using websites such as Ancestry, Staffordshire BMD and the National Archives.

Climbing the spiral staircase to floor 7 of Birmingham’s Central Library, in order to “see what I could find” led me to realise that I was wholly unprepared for what I could find. Whilst I cannot say that I found any particular skeletons in the closet for my family’s history, I can say that although I loved being surrounded by parish records of Aston and Witton, using the special foam rests and putting my belongings into the locker, I honestly had no idea what I was doing, and did not venture up the spiral staircase again.

When I became a secondary school History teacher, I was determined to use my family history archives in the classroom as much as possible. Being very lucky to have my great grandfather’s First World War attestation papers and war records, I used these as part of my 1914-18 unit of work following soldiers through the Western Front.

The ‘reality’ of the war, based on the fact that their teacher was related to this ‘real person’ proved to be engaging and enriching for my pupils year on year. They relished the opportunity to look through Thomas’s records and decipher the cursive handwriting.

However, it occurred to me that my use of archives in the classroom was somewhat limited, given the wealth of items that are held in each archive around the country! In working with a group of Birmingham City University’s PGCE Secondary History, I was determined to ensure that they had some knowledge and confidence in accessing and using archives, both national and local, in the classroom. Following a day’s workshop with Corinna Rayner and Martin Phillips, I posed each of the following questions to them under the guise of “What advice would you give to fellow History teachers who were interested in using the archives?” I have detailed their responses and ideas below:

Where do you start if you want to use the archives?

First of all, do some research in your chosen topic area (or proposed unit of work). Have an idea of the enquiry you may put to pupils. Start by exploring the Birmingham City Council’s archives website which details logistical information such as opening times and e-mail contacts. It is a good idea to e-mail the team, who are more than happy to talk through your ideas and discuss what archives may be of some use in your classroom.

BCU’s trainees also recommend that you spend a bit of time exploring the Archives online catalogue. Whilst the is won’t necessarily show you the documents themselves, it will give you sufficient detail to know what is available, which you can then discuss with one of the library’s archivists. If you’re unsure of using the catalogue, take a look at this video guide.

Remember, archives by nature are vast and overwhelming! Documents are catalogued in many different ways so planning and preparation in advance of venturing to an archive are vital. Trainee Andrew states, “Do not be afraid to seek advice from the people that work in archives they are more than happy to help and could support you in finding what you are looking for a lot quicker than you would be able to by yourself.”

What are your top tips for using the archives for planning a unit of work?

During our workshop BCU trainees were tasked with planning a unit of work based on a collection within the Birmingham archives. Through using the Connecting Histories website in a matter of hours they were able to map out a sequence of lessons based on the online resources available.

In an almost unilateral response to the above question for “top tips”, trainees suggested that the research guides are the ideal place for teachers to begin. Abbie explains, “[the research guides] are a good starting point and have information on where you can look in the archive for more detail.” The research guides themselves cover a range of topics, from women’s suffrage movement to the nature of religion in the city. They are, for us teachers, a ready-made guide complete with source material, contextual information and key historical questions to help guide our planning. During this task, Hamza realised that the research guides “already show you what [the archives] have and how you can incorporate them into the unit of work.”

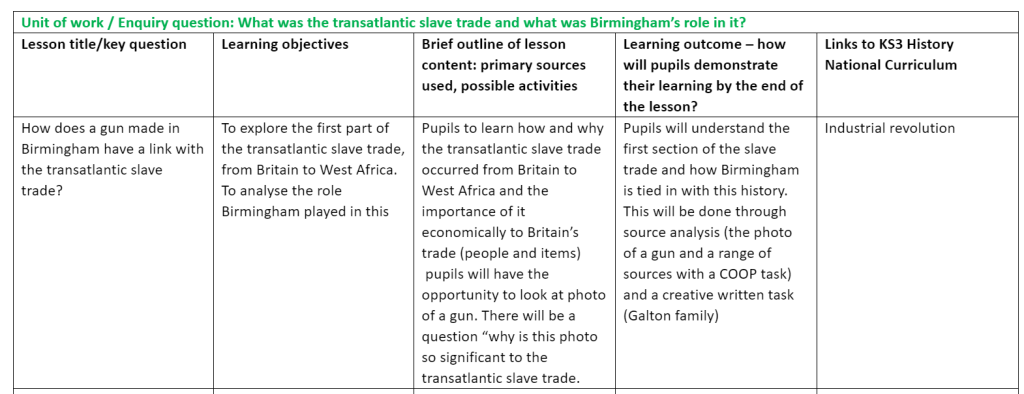

Example 1 – using the Slavery and Abolition research guide

Example 2 – using the Votes for Women research guide

How could using archives support pupils’ understanding of historical evidence?

Why go to the effort of trawling through pages and pages of documents in your local archive (or their online collection!) when you can just as easily use a textbook?

Shoib suggests that “the use of historical artefacts/archives can help your planning and teaching, through innovative use of new and different resources, and artefacts.” In other words, you may be surprised at what you find out when using these resources, which may in turn challenge your views on a particular topics.

Bradley continues, “Archives provide a plethora of information, some of which may refute the overarching narrative. This means that alternative perspectives can be accessed, and this helps students to create balanced and sustained arguments.” For example, in the Slavery and Abolition research guide, one of the key questions is “In what ways did the industrial West Midlands profit from slavery; and, how did antislavery organisations develop to resist the trade?” This would address an important reality in the study of abolition of the slave trade and later slavery in the UK and allows pupils to consider the contextual nature of the debate.

Abbie also points out that this is a useful task to do with pupils as it support their “understanding why different people or groups can have different interpretations of the past e.g. a suffragette vs a police report of the same event.” A skill we can all agree is useful in an age of social media and “fake news”.

Furthermore, Andrew points out that the “use of archives gives pupils a more realistic understanding of the craft of a historian… In this way we can move pupils away from an understanding of historical evidence that focuses on the limitations and bias of sources and more into a place where they can view historical evidence as more useful contexts and for specific enquiries.”

How would this link with the demands of the KS3 History curriculum?

The 2014 National Curriculum for KS3 History includes “a local history study” as part of its statutory requirements, with an example of how to do this given as assessing how their locality reflects aspects the national narrative across a broad or narrow period of time.

Giving pupils a local historical context for historical events is almost automatically engaging, as Bradley states it “allows pupils to make sense of the places in which they live.”

Increased engagement in the topic may lead to opportunities for you to broach complex historical concepts; the familiarity of the local area I believe can begin to break down some barriers to learning in the History classroom.

Helen Elliot, Teaching Fellow and PGCE/PGDE Secondary History Subject Tutor, Birmingham City University, and students of Birmingham City University PGCE secondary history course.

![Slide from a lesson used by Helen with her students. The title reads “What did the army need to know about its recruits?”. Included on the slide are two photos. One is a sepia portrait photo of a soldier labelled ‘Miss Wilson’s Great Grandad – Thomas Berrington who fought in WW1.”. The second is a formal group photo of soldiers in uniform, and on it a caption reads “RESERVISTS [illegible] 1st GRENADIER GUARDS MAY 1921”.](https://theironroom.files.wordpress.com/2021/06/image-1-1.png?w=480)