Can any of us in 2024 really imagine the psychological impact of World War One – millions dead, many more wounded and injured physically and mentally. The understanding of the unwritten agreement between humans regards how to treat one another, completely shattered.

In the often overlooked first paragraph of Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence, first published in 1928, the voice of the narrator states – ‘Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically. The cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins.’ One reading of the passage could be a comment on the psychological and social aftereffects of conflict never previously seen on such a scale.

How then did individuals and the societies they lived in decide to react to the residual emotional wrench and tumult of conflict. It could be argued the Sons of Rest movement was as a direct response to the traumatic fracture of the world and the call for collective male psychological repair so much needed.

The Sons of Rest is a social organisation formed in Birmingham in 1927 to provide leisure facilities to men of retirement age. A group of World War One veterans convened in Handsworth Park – one of the group, Lister Muff who has a plaque dedicated to him in the Handsworth Park building, put forward the proposal to start the organisation. Another, W. J. Ostler suggested the name, highlighting they had all been ‘sons of toil’ during their lives. A melding of the allusion to the biblical and the military in the name – ‘Sons Of’ inferring scripture passages referencing the Son of God. Rest referencing the euphemism employed as a mark of respect to those who did not survive the conflict – those at rest.

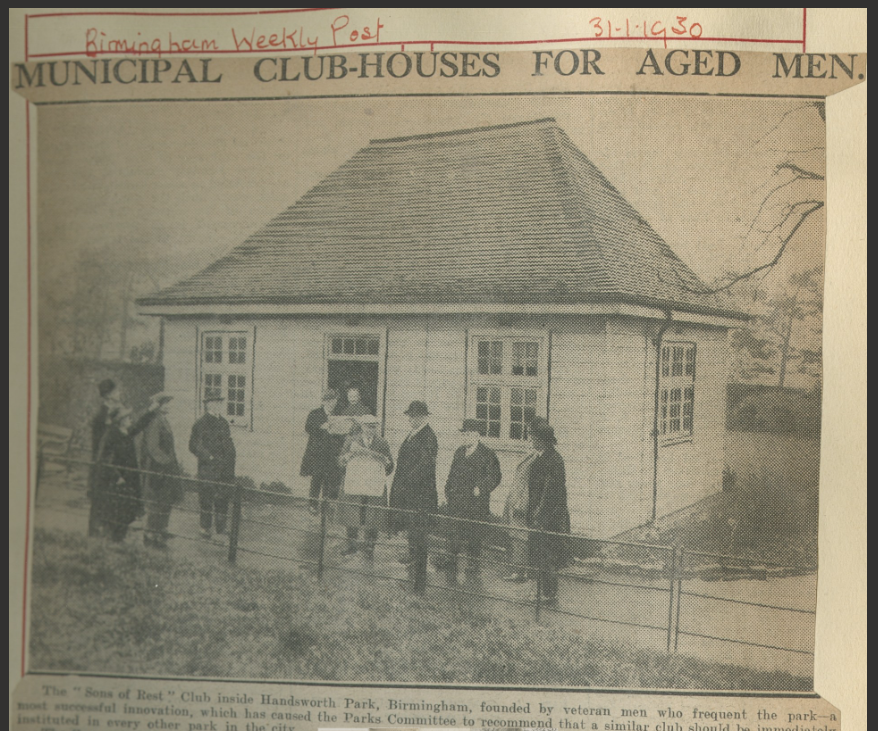

The original meeting place in Handsworth Park was an old cab driver’s shelter in the summer and the bowling pavilion in the winter. The first purpose-built building was opened in Handsworth Park in 1930 after funding appeals were made along with support from Councillor George F. McDonald, Chairman of Birmingham Corporation Parks Committee.

Sons of Rest premises located across Birmingham and the surrounding Black Country were typically located in the vicinity of a park or other green wooded spaces providing solace and peace. Men would gather to chat and to participate in activities such as dominoes, draughts and other board games. Latterly, several clubs extended membership to women.

At its zenith, the Sons of Rest had well over 3,000 members and up to 29 premises. Several of the buildings survive and remain in use today.

To find out more, you can read ‘’Sons of Rest’’ : History of the Birth and Growth of the Movement in Handsworth Park, 1927 – 1937 on level 4 of the library.

Paul Taylor, Archives & Special Collections Co-ordinator